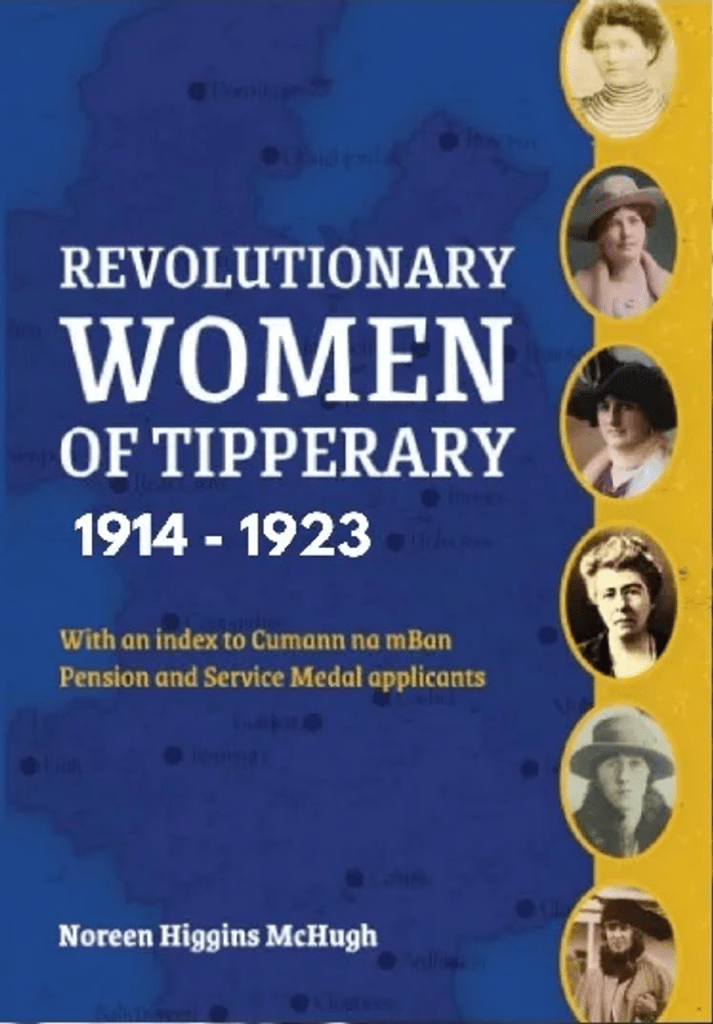

Any substantive contribution that illuminates the role of women in the Irish independence movement deserves recognition, particularly when it uncovers their personal sacrifices and achievements. In her 2024 publication, Revolutionary Women of Tipperary, 1914–1923, Dr Noreen Higgins McHugh offers a solid addition to the growing corpus of scholarship on revolution in Ireland through a gender lens. By focusing on a single county, McHugh effectively engages broader national chronologies, thus enriching the field both in depth and scope.

This volume is a product of sustained research, facilitated in part by the enhanced availability of key collections, such as the Bureau of Military History and, most notably, the cataloguing and digitising of the files of the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC). The latter in particular has opened new pathways for scholarly inquiry and McHugh makes good use of these resources, navigating various scales of analysis, interlacing the local and the national. Her work explores several dimensions of women’s involvement: participation in major political events, the growth of national and local activism, the gendered complexities of pension verification processes, and, crucially, women’s individual identities, familial circumstances, and lived experiences.

Inspired by the personal story of Maureen Power (Coolnagun Tipperary), McHugh undertakes the formidable task of collating and interpreting a vast array of archival material, presenting it in a clear and accessible manner. Her study addresses two central historiographical challenges: first, to provide a comprehensive account of Cumann na mBan activities in Tipperary (set against the national background) from its inception through the post-Civil War period; and second, to document the lived experiences of women, both as active participants and as applicants for military pensions. These aims are supported by structured chapters facilitating reader engagement and a series of appendices detailing information that is, by nature, dense and complex.

The book itself is divided into two major parts. Part I (Chapters 1–10) traces the development of early twentieth-century Irish nationalism with a particular focus on female activism. McHugh charts the emergence and evolution of Cumann na mBan, interweaving the experiences of women from Tipperary and East Limerick within a broader national chronology, from World War I and the 1917 Cumann na mBan Annual Convention to the anti-conscription campaign and the 1918 general election. The Soloheadbeg ambush (January 1919), widely considered the opening salvo of the War of Independence, introduces the role of Mrs Marian Tobin who sheltered the ambush’s participants. Advised by Séamus Robinson not to join Cumann na mBan formally, her involvement underscores the breadth of women’s contributions and the limits of formal organisational membership as a measure of activism. McHugh continues to embed the actions of Tipperary women within the unfolding national story, covering the War of Independence, the Truce and Treaty negotiations, and the Civil War. She provides an analysis of the Treaty debates, including a list of Cumann na mBan delegates who attended the 1921 and 1922 conventions.

Particularly notable is McHugh’s emphasis on the personal hardships endured by women: from intelligence gathering and arms transport to their presence at ambush sites. She also highlights the “invisible” labour of domestic support roles: clerical work, catering, and the financial burdens borne within households. One section poignantly explores the “loss of loved ones” as articulated in pension applications. This is a welcome mention as these losses are somewhat less visible than those outlined in the claims lodged by the dependants’ relatives and they can be hidden in the individuals’ narratives. The “Aftermath” section is especially valuable, documenting the arrests of Tipperary women in March and April 1923. Here, McHugh builds on the work of Sinéad McCoole and Ann Matthews, expanding their findings with newly available MSPC material. She also sheds light on women who were injured or bereaved during the conflict and includes a compelling discussion of the economic precarity faced by female veterans in the years following the Civil War.

McHugh details the bureaucratic and ideological challenges women encountered under military pensions legislation. A critical contribution is her inclusion and analysis of John McCoy’s General Principles to Interpret ‘Active Service’ for Cumann na mBan Members. This document established a set of narrow criteria to assess women’s activities and their claims for service. Critically, it reveals the dissonance between traditional, male-coded understandings of “active service” and the less visible yet essential roles performed by women. McHugh exposes the misogynistic attitudes embedded within the verification of women’s claims, which compounded the structural barriers they were already facing in society.

Additional challenges, such as emigration, marriage, and changes in surname or residence, are discussed, underscoring the difficulties of tracing pension applicants. The story of Maureen Power, who died in 1925 before becoming even eligible for a pension, serves as a powerful reminder of the many women whose service remained unrecognised and unrewarded. This also concerns women who passed away during the years it took the Army Pensions Board to issue a final decision regarding their claims. While McHugh generally succeeds in making the complex legal framework accessible, a point of confusion should be noted. On page 177 the first Military Service Pensions Act is mistakenly dated to 1927. It was the MSP Act,1924 that first granted pensions to those who had served in the National Army during the Civil War. It was under the 1924 legislation that Dr Brigid Lyons Thornton received the only military service pension awarded to a woman in the National Army, in recognition of her role as a medical officer. Lyons remained the sole commissioned female officer in the National Army until 1981 when the Irish Defence Forces saw the commissioning of female officers following the 1979 Defence Amendment Act. The Military Service Pensions Acts of 1924 and 1934 addressed ‘active service’ claims, while the Army Pensions Acts (1923, 1927, 1932, 1937, and others) covered claims related to wounds, disability, and dependency.

Revolutionary Women of Tipperary, 1914–1923 exemplifies the scholarly potential of newly accessible primary sources to drive both national and local research. McHugh’s work makes a good contribution to the historiography of revolutionary Ireland. It affirms the importance of regional studies and stresses the necessity of integrating women’s experiences into broader national histories. Through this careful collating work and synthesis of dense material, McHugh has produced a work aspiring to become a well-grounded reference for research on gender and revolution in Tipperary, and the importance of the local dimensions of Ireland’s struggle for independence. Looking ahead, the completion of the cataloguing of women’s pension application files (2023) raises the prospect of future work on the dependency claims submitted by the mothers and widows of deceased volunteers. A supplementary study in this area would offer further insight into the gendered dynamics of recognition, loss, and compensation after the revolutionary period.

Biography

Cécile Chemin is Senior Archivist in the Military Archives of Ireland and Director of the Military Service (1916-1923) Pensions Archive.

Trained as a linguist in France (English and American Languages and History, majoring in historic linguistics), she became a professional archivist in Ireland in 2005, earning a H. Dip. and M.A. from University College Dublin. Her professional work has extended across academic institutions, private consultancy (institutional records), local government (Wicklow, Kildare, and Meath County Councils), before finding employment with the Department of Defence and Irish Defence Forces. Her interests include linguistics and the role of archives in social accountability, the public good, sustainability, and human rights. Cécile is a member of the Irish Committee of the Blue Shield (Cultural Property Protection during conflict and disaster) and of the International Council on Archives.