This book is so good, I am finding it hard to do it justice in a short review. Jackie Uí Chionna’s exhaustive research has unearthed a wealth of heretofore unknown material, important and fascinating in equal measure, and the crowning accomplishment is that the telling of the tale is wrought in a colourful and accessible way. So, here goes…

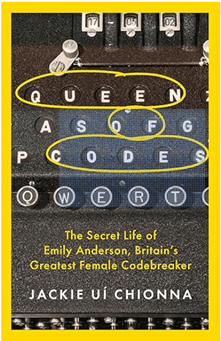

If the introduction to an historical biography depicts a funeral scene conjuring up images of a foggy John le Carré movie, that’s a great start, and it’s exactly what the introduction to Jackie Uí Chionna’s Queen of Codes does. It ignites and excites your curiosity and compels you to motor on posthaste. Yes, dear reader, Dr Uí Chionna, has done the reading public a massive favour. And surely that is what we all want, and indeed deserve – accessible history books, meticulously researched and written by trained historians, but written in such a way that the reader comes away indisputably the better for the experience.

Recognized, during the interwar years, as one of the best cryptanalysts in the world, Emily Anderson served in every iteration of the British intelligence service until her retirement in 1950 as its most senior female codebreaker. As you turn the pages of Queen of Codes, you will slowly get the measure of this remarkable and enigmatic woman, so deserving of a biography, and indeed, Uí Chionna has given us a masterclass in historical biography, especially one about an elusive character who somehow escaped scholarly examination; a person whose stellar linguistic, musical and mathematical abilities made her a world-class cryptanalyst, most notably in unravelling the nuances of diplomatic correspondence.

When it comes to equality though, brilliance was too often trumped by gender, and Anderson had to fight to receive the same pay and promotion opportunities as her male colleagues. And isn’t it odd that Emily Anderson, Britain’s greatest female code breaker, remained unknown to us. But then again, as Uí Chionna reminds us, so many early memoirs of the heady days of codebreaking were written by men, and they, in effect, defined that history.

Anderson’s childhood appears to have been quintessentially Victorian and Edwardian, and unquestionably privileged. As the daughter of Professor Alexander Anderson, renowned physicist and president of Queens College Galway, later University College Galway, she lived quite the Alice Liddell utopia in the beautiful college grounds. Not quite Oxford’s dreaming spires, but certainly a world apart from life beyond its gates.

Throughout her BA degree in Modern Languages, Anderson amassed many awards and scholarships before stepping onto the European stage to continue her studies. One can only imagine the excitement and anticipation, in 1911, of the twenty-year-old Emily, landing into a vibrant Berlin of around two million inhabitants from a provincial Galway City of approximately 13,000; from a university of a few hundred to a university of several thousand. Her subsequent move to the University of Marburg was cut short by the outbreak of World War One, and she returned to a University College Galway almost depleted of students and with no prospect of an academic position.

Like so many twenty-three-year-olds today, Anderson found a teaching job abroad in 1915, taking up the position of Modern Languages Mistress at Queen’s College, Barbados. In a sequence of events strangely redolent of The Thirty-Nine Steps, encompassing World War One and the 1916 Rising, she returned to Galway in 1917 to take up her appointment as Professor of German. It was in this eminent position that Anderson was secretly approached to train as an intelligence officer to decipher encoded German wireless messages, something she willingly agreed to do, as her brother was by then in a German prisoner of war camp. This initial recruitment to the military intelligence service would shape the remainder of Anderson’s life and career.

Codebreakers who could decrypt German signals intelligence on the Western Front were urgently needed, and with men engaged in active service, women with the right skills and qualifications were recruited. Anderson found herself in the army’s cryptographic section MI1(b) in 1918. From Galway University academic to secret cryptanalyst in France, her life had taken a new trajectory, and her brilliance was noted by the fledging intelligence service who actively sought to continue her employment in the post war intelligence arena.

Anderson’s unparalleled acumen in book building – the first phase in code breaking – earned her the position of Head of Italian Diplomatic Section, in 1927. Fascinatingly, she used her talent for finding ‘cribs’ – material that suggests the possible content of an encrypted message – to decode the ciphers often employed by the Mozart family in their letters. Notably, her translation work, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, remains the standard English-language version today. With twenty years of interwar intelligence experience behind her, Anderson commenced her World War Two service as a senior codebreaker of eminence. By 1939, she was already decamped to Bletchley Park as the only female Senior Assistant in the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS).

1940 would be an intensely stressful year, comprising as it did the German invasions of Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands in May, Italy’s entry into the war in June, the fall of France, and later in that month, Germany’s defeat of the Allies in Europe. The pressure was on Anderson and her colleagues to extract vital information; a dauntingly complex task which involves translating intercepted morse codes to their alphabetical and numerical equivalents, before breaking the cipher in the appropriate language (German or Italian) and finally using your brilliance to capture the nuances applied to wartime diplomatic correspondence. Always conscious of the greater good, Anderson chose to leave Bletchley Park and her work in Italian diplomatic traffic, to go where she was most needed. This time it was to the Cairo and Combined Bureau Middle East, where she would work on Italian military traffic. Here, she and her team cracked Italian battle plans, resulting in Allied victory in the East African campaign.

One never hears as much about Berkely Street, Anderson’s next place of work on returning from Cairo, as one does about the more romantic Bletchley Park. Altogether more diminutive and demurer, Berkeley Street, discreetly situated over a dress shop in London, was a powerhouse of diplomatic signal intelligence, Anderson’s metier, and this is where she would conduct the rest of her World War Two intelligence activities.

Never one for seeking the limelight, by choice rather than from reticence or modesty, Anderson was perhaps more consumed by her second career as a musicologist. For her, retirement from intelligence work gave her the time to concentrate on her mammoth translation project, The Letters of Beethoven, an undertaking requiring her undisputed prowess as a codebreaker. Tellingly, this three-volume magisterial work remains the definitive one.

This book is a treasure with wonderful and colourful anecdotes beautifully woven into the narrative. It has brilliant insights from workaday to everyday, including the acceptance, or otherwise, of a senior and highly accomplished woman operating in a male dominated sphere, an enigma of another class altogether, to be cracked, and one which Uí Chionna has achieved magnificently. This review is at best a skeletal scaffold, and I hope it encourages you to read Queen of Codes in its entirety to discover all the things I desperately wanted to allude to, but couldn’t.

Berni Dwan

Holds a BA in English and History from UCD and an MSc from Trinity College and has taught English Literature, Creative Writing, History and Journalism in Dun Laoghaire Adult Learning Centre and Dun Laoghaire Further Education Institute. She is a Professional Member of the Irish Writers Centre, where she has delivered two poetry courses.

Radio dramas:

Awakenings: https://listenagain.org/?p=50932

A Fishy Tale of Sound and Fury: https://listenagain.org/?p=48906

Alarm Bells:https://listenagain.org/?p=42163

History series:

Hedge Schools Beyond the Shrubbery. Eight episodes on: https://listenagain.org/?cat=23087

Hungry Gap, Fat Friars, Food Poverty: Three episodes on: https://listenagain.org/?cat=22788

Literary series:

Seven Stages for Seven Ages. Seven episodes on: https://listenagain.org/?cat=24005

Growing Up Between the Dustjackets. Eight episodes on: https://listenagain.org/?cat=21136